So long lives this, and this gives life to thee. So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, When in eternal lines to time thou growest: Nor shall Death brag thou wander’st in his shade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou owest Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,Īnd every fair from fair sometime declines,īy chance or nature’s changing course untrimm’d Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,Īnd summer’s lease hath all too short a date: The information of medicine and health contained in the site are of a general nature and purpose which is purely informative and for this reason may not replace in any case, the council of a doctor or a qualified entity legally to the profession. Check out the "Love" theme for more on that.The following texts are the property of their respective authors and we thank them for giving us the opportunity to share for free to students, teachers and users of the Web their texts will used only for illustrative educational and scientific purposes only.Īll the information in our site are given for nonprofit educational purposes

Certainly this poem has some of the qualities of a love poem, but, to say the least, this poem isn’t just a poet’s outpouring of love for someone else. The main reason is that sonnets, at least before Shakespeare was writing, were almost exclusively love poems. Don’t be fooled, though: beyond the form, this is not your stereotypical sonnet. In this case, the closing lines have the feel of a cute little poem of their own, making it clear that the poet’s abilities were the subject of this poem all along. This poem also has the uniquely English twist of a concluding rhyming couplet that partially sums up and partially redefines what came before it. Here Shakespeare switches from bashing the summer to describing the immortality of his beloved.

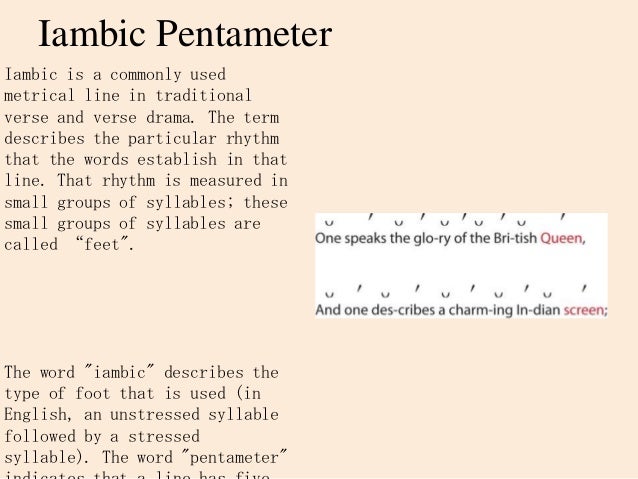

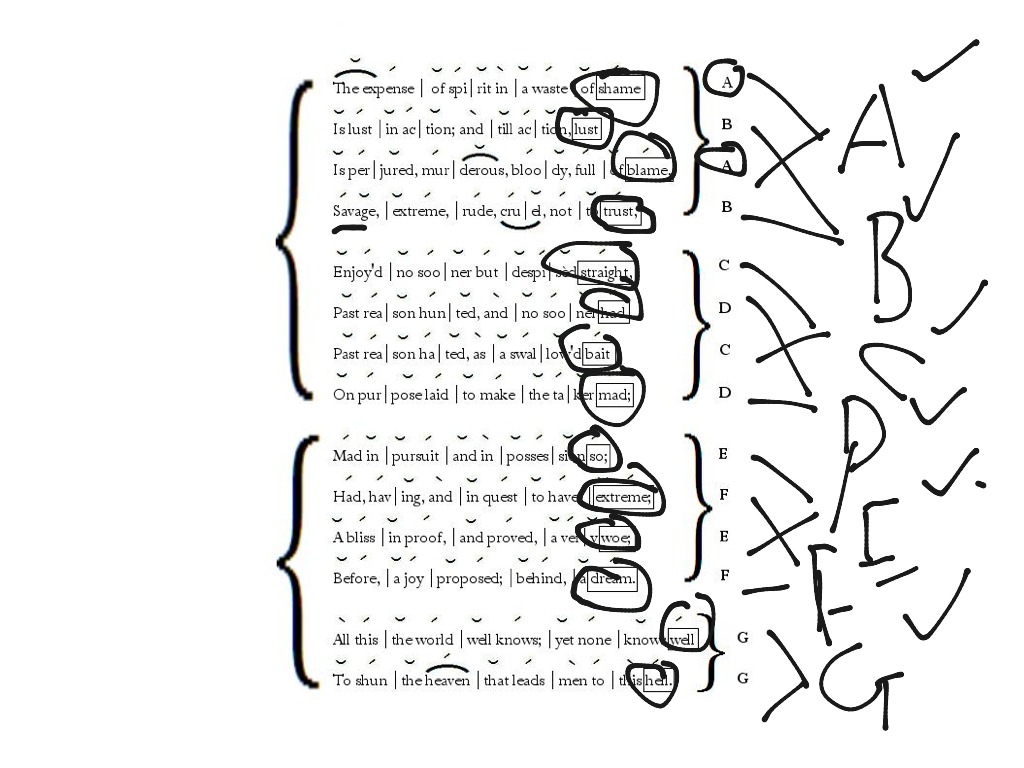

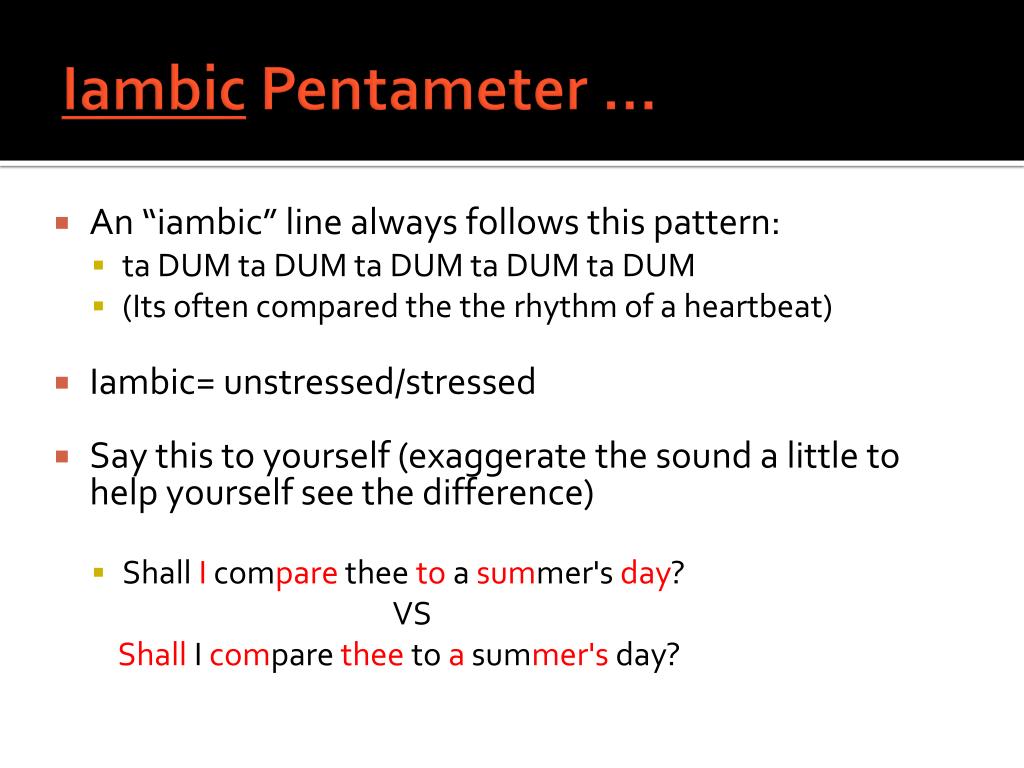

Just as in older Italian sonnets by which the English sonnets (later to be called Shakespearean sonnets) were inspired, the ninth line introduces a significant change in tone or position. The form of this sonnet is also notable for being a perfect model of the Shakespearean sonnet form. There are two quatrains (groups of four lines), followed by a third quatrain in which the tone of the poem shifts a bit, which is in turn followed by a rhyming couplet (two lines) that wraps the poem up. There aren’t even any lines that flow over into the next line – every single line is end-stopped. With the exception of a couple relatively strong first syllables (and even these are debatable), there are basically no deviations from the meter. This is a classic Shakespearean sonnet with fourteen lines in very regular iambic pentameter. A Shakespearean Sonnet in Iambic Pentameter

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)